On February 10th, I had the opportunity to go see former Senator George Mitchell speak on a panel at Queen’s University Belfast with Monica McWilliams (former leader of the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition) about their memories from the peace talks that culminated in the landmark 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which helped bring peace to Northern Ireland. Listening to Senator Mitchell speak about his role as Chairman of the talks, I was immediately struck by his verbal skill. When faced with a surprising question, he would pause for the most fleeting of moments to gather his thoughts, and then launch into a measured soliloquy in which not a word was out of place and which seemed to always end gracefully. Listening to him extemporaneously thread his words into artful, precise sentences carrying intricately linked ideas that cascaded from one to another in a way that was simultaneously orderly and natural-feeling was quite remarkable. The man simply radiated equanimity, gravitas, and intelligence, possessing a quiet but palpable charisma.

Many of the questions that were posed to Senator Mitchell asked him to speak to whether the successful efforts to end the violence in Northern Ireland offered lessons that could be applied by intrepid mediators in various other conflicts around the world. One point that he returned to repeatedly was the idea that while negotiators working on other conflicts could certainly learn from studying the conflict in Northern Ireland, all conflicts are different and are likely to resist a standardized approach. Furthermore, he argued that an undue focus on mediators like himself and mediating strategy in general was missing the point, because a conflict can never be resolved unless all the parties to the conflict are committed to its resolution-absent that crucial precondition, it doesn’t really matter what the mediator does. The most brilliant mediator in the world cannot compel or cajole belligerents to make peace if they themselves do not want it.

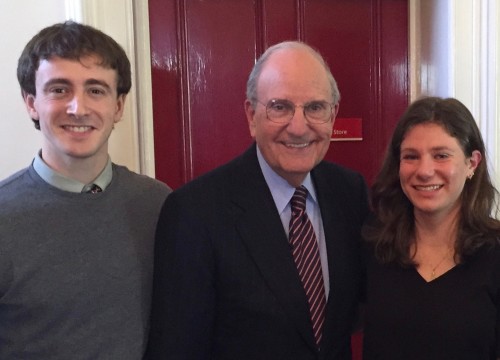

After his talk, I had the chance meet Senator Mitchell and then sit in on a film interview of him conducted by Azza Cohen, one of my Mitchell Scholar classmates. The interview was much more personal than the panel discussion, with Azza gently probing Senator Mitchell’s motivations and memories not just from the period in which he lead the negotiations, but also from earlier in life. One thing that really stood out from the interview was Senator Mitchell’s emotional discussion of his parents and the sacrifices they made for him. His father was an orphan of Irish descent, and his mother was an immigrant from Lebanon, a Maronite Catholic. His father worked as a janitor, and his mother worked in the paper mills of central Maine while also performing double-duty of a homemaker. Neither had a formal education, and yet they managed to ensure that each of their five children received a college education. Neither could have imagined that one of their children would rise to become Majority Leader of the United States Senate, and yet that is exactly what happened. It’s a remarkable testament to the social mobility that defined the America he grew up in, and which I hope will define the America of my lifetime as well.