One of the joys of this Mitchell year has been the opportunity to explore Ireland and to encounter the depth of its spiritual and historical heritage. Just by living here over the past 7 months, I have been well exposed to the enthusiasm of the Irish for all things Irish, but two trips this spring semester have particularly sharpened my appreciation for the Irish emphasis on ritual and historical memory.

The first was in late January, when a friend from Maynooth and I went out to County Mayo in the west to climb Croagh Patrick, the mountain upon which Saint Patrick famously made a forty-day retreat, fasting, praying for the conversion of the Irish, and living in a cave amidst the harsh elements. Climbing “the Reek,” as it is called, is a traditional spiritual rite of passage for the Irish—a pilgrimage of penance, sacrifice, and prayer and an act commemorating the saintly man who brought the Catholic faith to Ireland.

To this day, on “Reek Sunday,” the last Sunday in July, tens of thousands of pilgrims from all over Ireland flock to follow in the footsteps of Saint Patrick, while countless more go every other day of the year. Amazingly, a substantial percentage of them, including many elderly, make the whole trek barefoot—and this climb is no joke, filled with steep inclines and many sharp and loose rocks! Though my friend and I did not go barefoot, we certainly faced our own share of challenges, including heavy rains and, at one point, 70-plus mph winds on a flat about halfway up the mountain. The experience was humbling, especially when I considered that millions of Irish throughout history, often much older than I and with much less than sneakers and a rain jacket, had completed the climb successfully, let alone that Saint Patrick had survived those conditions for forty straight days. It was a sound reminder that the climb is not so much about the physical ascent as it is about the spiritual.

The second trip was a recent excursion down to the south of Ireland, where I visited Cork (the home of Peter, another Mitchell Scholar!), Cobh, and Kinsale. One could say much about the rich character of all three places and the unique spirit of the southern Irish, who hold firmly that Cork is the “real capital of Ireland.” But a brief afternoon trip I took out to the beautiful seaside village of Kinsale was particularly memorable. My scholarship coordinator at Maynooth kindly connected me with her brother, who lives nearby and gave me a tremendous tour of Kinsale Harbor, explaining with impressive detail the deeply nuanced history of the area.

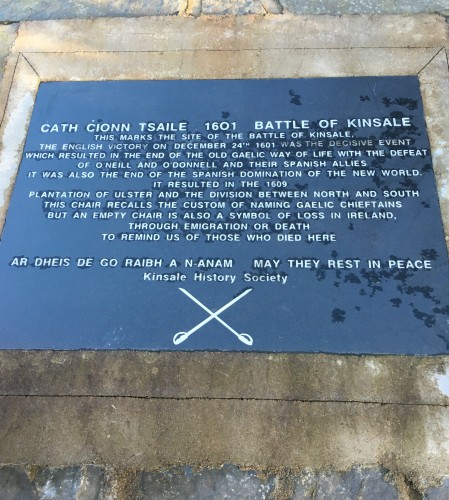

Throughout the tour, I could not help but be struck by the enduring persistence of the Irish in working to maintain and preserve their identity, culture, traditions, and historical memory. Kinsale is famous for being the site of the 1601 Siege of Kinsale, which was a major battle between Gaelic tribes, supported by the Spanish, and the English, who were seeking to expand their control over the entirety of Ireland. After a fierce and highly tactical fight, the Irish and Spanish ultimately lost, marking a major turning point in Irish history, for the English had finally broken the Gaelic tribal governance system and their way of life. (And in important ways, that English victory opened the door to further westward colonization in the New World, which may well have been entirely Spanish-speaking had the Spanish been victorious at Kinsale and held off the British.) Yet to this day—especially in the wake of last year’s 100th anniversary of Irish independence—the Irish are proud to commemorate that battle and the persistent efforts of their ancestors across the centuries to defend and preserve their religious and political sovereignty and heritage. In a technocratic age that can tend to look to the past with skepticism and distrust, the sincerity of the Irish reverence for their spiritual, political, and cultural heroes of years bygone is refreshing and inspiring, and, indeed, something I will be proud to take home with me.

A cold and rainy selfie from the top of Croagh Patrick outside of the church and shrine to Saint Patrick!