“Well I found my Uncle Dan McCann,

Very good for a shantyman,

He has a seat in Congress, and he’s saviour of his clan

He helps to write America’s laws,

But his heart and soul is in Ireland’s cause,

God help the man who opens his jaws

To my Uncle Dan McCann!”

– My Uncle Dan McCann by Mick Moloney

Dear Reader,

I’ve been thinking a lot about Irish American political influence and assimilation lately. The stanza I chose for this entry is from “Far From the Shamrock Shore: The Irish American Experience in Song” by Mick Moloney. The song the stanza is blends real and idealized aspects of mid-19th century Irish immigration to America. Dan McCann, the narrator’s fictional uncle, possesses the traits frequently attributed to Irish immigrants of the time: he is boastful, physically suited to hard labor, and inclined towards singing and dancing. The turning point of our protagonist comes with the outbreak of the Civil War, where he enlists with the Irish Brigade (“the Fighting 69th“) whose exploits are covered both positively and negatively in many other songs of the time.

The Civil War was a turning point for the Irish because their service, which occurred mostly on the Union with some degree of reluctance, enabled them to assert themselves more confidently in political and social life. This coincided with the emergence of machine politics in many urban centers where the Irish were concentrated. Among others, these factors helped the Irish win political struggles against the nativist coalitions that had long opposed their presence, sometimes violently. This sense of upward mobility and the willingness to defend it is where we last see Uncle Dan in the song. He is at once a loyal American and an Irish patriot, a sophisticated congressman and a hardened fighter.

While these extremes may seem like contradictions, they accurately depict the complicated path assimilation often takes. Over time, immigrant groups struggle for acceptance, often have to shed blood to earn it, and after several generations some of their descendants end up arguing for the same restrictionist policies that their forefathers struggled against. The Irish experience is relevant because more recent immigrant groups continue to follow this cycle despite greatly changed geography, conditions, and circumstances.

Today, Irish Americans play a part not only in U.S. politics but also on politics in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. With the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement coming up, American investment in the future of the island is demonstrated by the attendance of several prominent public figures in the celebrations.

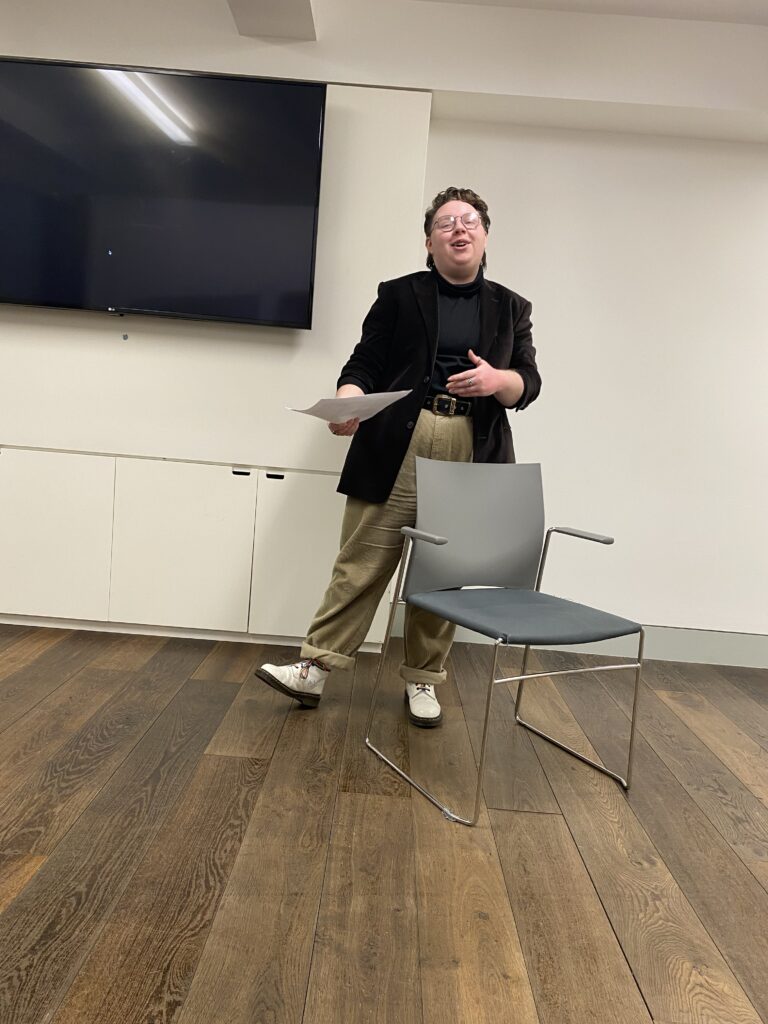

In other news, I’ve continued to enjoy the conversations and exposures to new perspectives and activities by the friends I’ve made here. Whether it’s dialogues about the role of social media with Asha, insights on class dynamics from Sarah, lectures on Oscar Wilde delivered by Mál, or wide ranging and dubiously connected rants with Ellie, my time here has been greatly enriched by the people the Mitchell program has connected and re-connected me with.