“And the prophet sings not of the end of the world but of what has been done and what will be done and what is being done to some but not others, that the world is always ending over and over again in one place but not another and that the end of the world is always a local event, it comes to your country and visits your town and knocks on the door of your house and becomes to others but some distant warning, a brief report on the news, an echo of events that has passed into folklore.” –Paul Lynch, Prophet Song (2023).

Meet my classmates! These people have been a consistently positive support network for me since September, and I’m proud to call them my friends. It’s an honor to intellectually spar with people who are so accomplished, passionate, and, most importantly, curious about the world and how to make it better. The breadth and depth of issues we tackle has only broadened over time, which challenges me to bring my A-game every day in the best way possible. I bragged about my classmates in my first blog post, but we finally took a nice group picture a couple weeks ago, so now I can recognize them properly.

But things change as much as they stay the same. The last several weeks have brought many changes to Belfast: the Sun rises earlier each morning, blooms of flowers are casting an ever-brighter hue across the city, and, in February, Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) returned to work at Stormont for the first time in over two years. The return of power-sharing between unionists and nationalists is certainly a positive development for Northern Ireland because the democratic will of its people has a chance to be properly realized. But strong policy outcomes are far from a guarantee, and actors from across Ireland are increasingly questioning whether power-sharing in its current form is the most sustainable foundation for Northern Ireland’s peaceful future. I recently committed to investigating this controversy with my dissertation, which allows me to combine my long-term interest in migrants’ political participation with my budding fascination with transitional justice, which I only discovered last semester.

Consociationalism and its Discontents

MLAs today continue to designate as unionist, nationalist, or “other” (neither unionist nor nationalist) when voting for legislation, as outlined by the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement. The consensus among researchers is that Stormont is a prototypical “consociational” power-sharing institution, in which unionists and nationalists are required to govern together. The theory of consociationalism was first proposed by the political scientist Arend Lijphart to ensure that each major ethnic group in a given state is guaranteed a meaningful say in government; without groups’ full participation, public institutions cannot function under this regime. In states like Northern Ireland—where ethnic identity is salient, and where a majority group historically weaponized political institutions as a tool of oppression against one or more minority groups—group-based political arrangements are considered a necessary element of reaching a negotiated end to violence. To remedy past injustice, consociationalism prescribes four institutional features:

- a “grand coalition” government, which includes representatives of all major groups;

- proportional allocation of ministerial portfolios and other government positions that reflect each group’s strength;

- “segmental autonomy,” meaning each group is delegated the power to run its own affairs in areas that are salient to their identity, and;

- “mutual veto” powers, which ensures that no one group can politically dominate the other.

While consociationalism may equalize ethnic groups’ political rights, is has attracted substantial criticism. Among the charges most applicable to Northern Ireland, it has been accused of entrenching ethnic identity (instead of promoting integration and/or the softening of traditional identity lines), undermining traditional democratic norms like electoral competition, and sidelining the preferences of “others,” whose policy votes mean less in comparison to privileged groups like unionists or nationalists. I believe that Stormont’s chronic dysfunction, paired with the major, recent demographic changes in Northern Ireland, makes it impossible for the will of the people to be properly legislated now or in the future without meaningful changes to power-sharing. Yet, the state’s largest political parties do not support any reforms at this time, in my opinion because the current system grants them an extraordinarily stable electoral base and disproportionately high legislative power to wield.

I feel called to understand how democratic will can be better realized through institutional reform here: I plan to investigate what institutional reforms have been proposed over time in Northern Ireland, why they were (or were not) implemented, and to what extent the preferences of the demographic “other” have been accommodated in the consociational regime. I’m also curious to learn if and how consociational institutions in other states have peacefully evolved over time to better accommodate “others” and reflect more traditional democratic practices. Researching this phenomenon feels urgent to me because I believe Northern Ireland’s policy issues, from its public goods to its transitional justice mechanisms, ought to be tackled by a government that is focused and interested in adapting to an ever-changing world. The current regime is not conducive to that kind of creativity, in my opinion. I love this place, and I believe that researching how to improve Stormont is the best way I can apply my expertise to promote its long-term welfare.

My Modules, Round Two

I’m taking three modules this semester: Dynamics of Reconciliation (DR), Forced Displacement, Conflict and Peacebuilding (FDCP, in Dublin), and a community placement with Shared Future News (SFN). While my first set of modules offered a sweeping overview of peace and justice studies, this second set has allowed me to dive into specific questions and case studies that most catch my interest. I’ve particularly enjoyed my work with SFN so far, through which I’ve published a research piece on transitional justice and two panel discussions: one featuring experts from peacebuilding scholarship and practice, and another featuring an Afghan artist, educator, and activist. I’ve appreciated the challenge of synthesizing and communicating nuanced academic theories to a general readership, honing my attention to detail, and distinguishing truly important details from fluff. My supervisor, Allan Leonard, has helped me strengthen my writing and identify my factual blind spots in ways that I haven’t experienced since my first days at Michigan State. I’m incredibly grateful for his mentorship, which I feel has already made me a better scholar. My publications have also allowed me to expand my theoretical knowledge and apply them to real-world, consequential scenarios. This has helped me feel like my work can, will, and is making a difference in people’s lives, which is simply awesome.

Breaking Out of My Shell

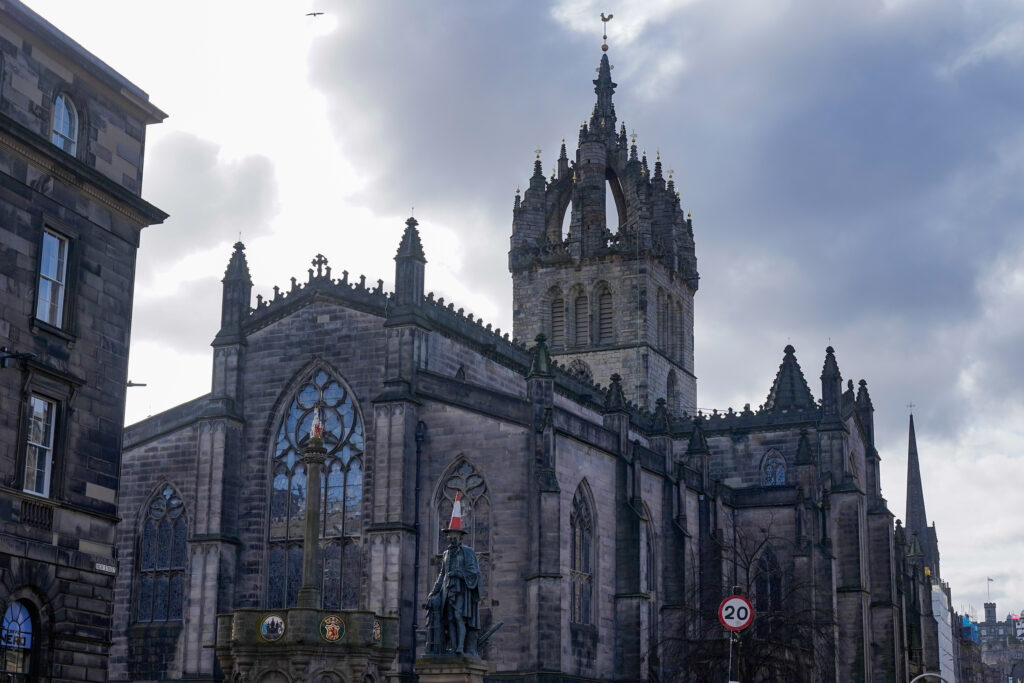

This semester has featured far more travel than the fall term. I visit Dublin at least once a week to attend my FDCP lectures, after which I join the Dublin International Peace Studies cohort for lunch. I’ve appreciated the opportunity to broaden my network by learning with these people, who, like my Belfast friends, are very diverse in terms of geographic and professional background. I’ve also taken a weekend trip to Galway, spent my reading week in Edinburgh, Scotland with Reed (my classmate and fellow American), and traveled to Rovaniemi, Finland, thanks to some cheap Ryanair fares. I’m more than comfortable staying in Belfast week after week, but I challenged myself back in January to break out of my comfort zone through travel, which I feel I’ve done quite well. Plus, I’ve captured a few decent photos along the way!

A World of Relationships

A few days ago, I heard from a good friend back in Lake Arrowhead. We chit-chatted about our normal topics, but at some point in our conversation, they mentioned that a mutual friend of ours had asked about me. I spend my days here living, exploring, critiquing, and absorbing Northern Ireland so intensely that I often forget that I don’t live in a vacuum. Anything I say or do branches out into the world, where it affects and is perceived by other people. That’s especially true in our age of social media, where my adventures can be shared with friends and family in mere seconds. As much as I’ve prioritized myself over the last eight-plus months, this exchange was a good reminder that my actions have consequences, good or bad. I believe I have an obligation to hold myself accountable, reflect on what impact I’m having now, and to imagine new opportunities to help others in the future. The world gains nothing if I keep my thoughts and reflections to myself, and I increasingly recognize how selfish it is to absorb knowledge without applying it towards the greater good. As I prepare to write my dissertation and finish my placement with SFN, I look forward to finding new ways to give back to the world at least some of what I’ve received.

If you’re on Instagram and wish to follow along with my Belfast adventures more closely, please connect with me here. If you’re an avid reader like me, and want to exchange book recommendations, add me on Goodreads here. If not, no harm and no foul!