“A person from Northern Ireland is naturally cautious.” -Seamus Heaney (2008), Irish poet.

For years, I wondered what it would be like to live in Northern Ireland (or the “North of Ireland,” depending on who you ask). My undergraduate program gave me many opportunities to explore the region through an academic lens, which gripped me from the start. Some of my assumptions were validated, but I discovered recently that many more were half-baked at best. I failed to grasp the unwritten, day-to-day nuances that make Northern Ireland so unique before I arrived. I also lacked a meaningful understanding of what ethnic conflicts look like elsewhere in the world, and how efforts to resolve them by the international community often create or perpetuate as many issues as they address.

My Course: World Peace. No Big Deal, Right?

This year, I’m studying Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation through Trinity College Dublin, which has a satellite campus in South Belfast. It always feels confusing to explain that, but I get a little better at it each time! I’m joined here by seven wonderful classmates from all over the world, representing China, Colombia, France, India, New Zealand, and the States.

Two parts of my course stick out as especially illuminating. First, it has shed light on unique dimensions of the Troubles that I would have never discovered if I studied elsewhere. For example, one of my professor’s areas of expertise is conflict-related forced displacement. In Northern Ireland, his research shows, tens of thousands of families were “burnt out” of their homes through the Troubles, forcing them to relocate elsewhere within Northern Ireland or internationally. Some later returned and/or rebuilt, but many never came back to their original homes. The impact of this forced displacement is alarmingly understudied in the literature concerning Northern Ireland, even though in practice, it continues to be a major source of psychological trauma and economic weight for survivors of the Troubles. Second, more generally, learning about the exclusion of input from conflict-struck communities in peacebuilding strongly resonates with me. When practitioners attempt to resolve conflict, they often employ the testimony of community stakeholders instrumentally, as a means to some prescriptive end they wish to impose. This usually has the effect of leaving deep-rooted conflict unaddressed, increasing the odds that conflict re-emerges later.

A Neat Little Town They Call Belfast

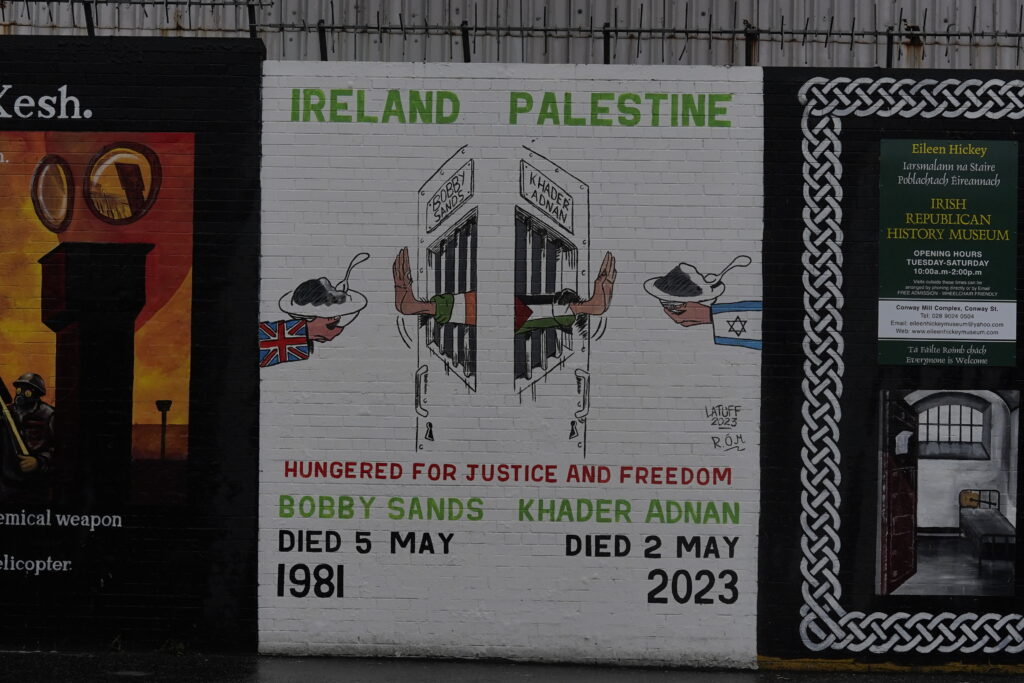

Belfast is the largest city I’ve ever lived in. While my love for this city grows every day, it has also been difficult at times to navigate, both literally and metaphorically. Taking the wrong bus route, getting off at the wrong stop, or wandering into the wrong business has become a near-daily habit for me at this point. Fortunately, I still see it as a positive because it gives me an opportunity to explore parts of the city that I otherwise wouldn’t have seen. Many things stick out to me as beautiful in Belfast, especially its lively art scene, architectural diversity, and well-kept green spaces. Public art—especially murals—are an important vehicle for locals to express their memories of the Troubles and interpretations of ongoing social issues. The tone, figures, and political messaging behind these murals evolves as you move from one neighborhood to the next. They are also incredibly responsive, often changing within weeks in response to domestic political debates or major global events. Art and memorials serve to mark community territory, grieve loss, and intimidate outsiders all at once. Even if a given mural depicts armed paramilitary volunteers donning balaclavas, they radiate powerful emotions and beauty that often leave me feeling introspective. It’s difficult to describe, and I hope to find the proper words for this phenomenon in the coming months.

Because of the polarizing messaging and unresolved conflict issues in Northern Ireland, I sometimes feel uncomfortable. But I also sense a distinct resilience in these streets. The Northern Irish people have been traumatized in more ways than I could fully understand, but no matter their background, most of them want the same basic things: peace and progress. To move forward without forgetting the past. Debates about the most ethical, inclusive, or effective way to do that vary widely, but difficult issues like this are the very reason my course exists.

This Island’s Natural Beauty

Peace and justice studies, ironically, take a heavy toll on me. It’s easy to feel distraught when I spend every day reading about the worst sins people can commit, and how much of that wrongdoing goes unpunished. I’ve long struggled to look out for my own well-being, which I chose to make a priority for myself when I embarked for Ireland. Indeed, I’ve found some reprieve from my disturbance in nature, where the only dissenting voices I hear are birds’ songs over the cool, misty air. I’ve spent many hours already in the Botanic Gardens of Belfast, along with Phoenix Park and St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin, but I’ve felt the greatest comfort outside city limits, in places like Killarney National Park.

Luckily for me, Ireland is filled with natural wonder. I felt inspired by the words of Kerri ní Dochartaigh, a Derry native who survived the Troubles, to find comfort in the wilderness. As she explains in her book, Thin Places (2021), “[When] I had managed to drag myself out into the natural world – to beaches and rivers, loughs and canals, fields and islands – everything felt different. I don’t know if I could honestly say that things felt better but I think that maybe I felt a little more at ease with the sorrow and anxiety that I was struggling to throw off” (original emphasis included, p. 22). Nature has a special way of putting things into perspective: I felt this at various points in my life, but I never knew exactly how to rationalize it. Billions of lives and events came before us, and countless more will follow our own time in this world, but the common thread through it all is our planet’s land. Land upon which our homes and temples stand; land that we explore; land that we trample, march upon, and exploit. But also land that we need, no matter what. Letting myself be swallowed up by nature helps me and my problems feel small in the best way possible. I hope to seek out more “thin places” as my Mitchell year goes on, because I crave feeling peace in our tumultuous social world.

My Path Ahead

Nearly two months have gone by since I first arrived in Ireland. In that short time, many things in my life have changed for better or worse. Adjusting to life in a new country, with different academic practices and social customs from America, has felt daunting at many points. I have also experienced isolation and homesickness to a new degree, even more than when I left my hometown for Michigan. I receive daily reminders of the opportunities, relationships, and socialization that I sacrificed over the years, and in all honestly, that can feel deflating. But to feel intense emotions instead of numbness, and to question myself instead of shamble ahead aimlessly, is also empowering. I believe it ultimately moves me forward. I also feel more reassured in my direction as I continue to read my literature and explore Belfast, where I see that conflict pierces all dimensions of human society. I regularly question what my ultimate career path will be and what tools I will use to address conflict, but I feel comfort in knowing that bridging divides fills me with wonder.