“All these years they’ve been like two little plants sharing the same plot of soil, growing around one another, contorting to make room, taking certain unlikely positions. But in the end she has done something for him, she’s made a new life possible, and she can always feel good about that.” Sally Rooney, Normal People, p. 272.

To me, deciding where to start is the most difficult part of writing a retrospective. Sometimes it’s best to take you on a journey from the very beginning: in this case, that would be Summer 2019, the very first time I visited Ireland as a wide-eyed college freshman. In other cases, I’d start from the end – here, the Mitchells’ most recent adventure on the Dingle Peninsula – and work my way backwards. But either of those options would lead me down a narrative rabbit hole that far exceeds the scope of this format. To that end, I’ll try to take you somewhere in-between.

It’s hard to sum up the first five years of my relationship with Ireland narratively, anyway, because of the pitfalls, bends, and moments of awe that have paved this trail. No moment or plotline is an adequate vehicle for that nuance. After all, it’s “not grand gestures” that make a life, but “all those moments through the days, weeks, months that don’t get marked on calendars with hand-drawn stickers or little stickers;” the “mundane details that, over time, accumulate until you have a home, instead of a house” (E. Henry, Funny Story, p. 329).

Sally Rooney puts it this way in Normal People: “I think we’re at that weird age where life can change a lot from small decisions” (p. 239). I cherish each of the small decisions that I, and others, made to lead me to this blog post. A few immediately come to mind:

- Studying abroad in Ireland during 2019. I could have instead chosen New Zealand, or Japan, or Canada, or nowhere at all, but I went with the place that most closely resembled the name my mother gave me. Would I have come here if my name was John, or Ryan, or Marty?

- Majoring in political science, even though history, sociology, and many other social sciences also piqued my interest. Would I have discovered, or capitalized on, my interest in the peace process without the tools of a political scientist?

- The assignment of Maysa Sitar as my “buddy” by the Social Science Scholars Program. Maysa’s encouragement and mentorship over the years was a cornerstone of my success at MSU that, on paper, set me up for professional success. And when she earned the Mitchell, it humbled me and showed that I could, and should, work boldly. Would I have heard of the Mitchell if someone other than Maysa was my buddy?

- The random assignment of Penny Graham-Yooll as my partner in the Senior Ambassador Program. Her warmth and stories of adventure from around the world have consistently inspired me over the years, especially while here in Belfast. Would I have felt brave enough to move abroad without Penny’s influence?

- Trina and Serena suggesting that I study at Trinity this year, instead of Queen’s, as I had originally intended. Would my research questions and relationship to the island be different if I had never met my classmates?

And none of these are as small, or impactful, as the first choice that I made:

- Applying to Michigan State University on a whim. I looked at schools in Alabama, Massachusetts, Virginia, and elsewhere, and I thought little of my alma mater before visiting. The only reason I saw East Lansing in January 2019, and committed to the school just days later, was because I had a free day between visits to other schools that I had cared about more. Where in the world would I be if I didn’t have that time? Where would I be without the privilege to take a cross-country college tour? Who would I be?

These small decisions, and countless others, make up a beautiful mosaic that I admire deeply. To explain what it means to me, I’ll focus on the main setting of my story. Belfast, my home for the last nine months. The city whose gravity captured me from that first July day and hasn’t let go. Where the peace lines continue to slam shut every night by sundown, despite the uplifting messages plastered across them. Belfast is a place that, itself, is somewhere in-between its past golden age (and times of trouble) and uncertain future. Tens of thousands of people still work day-in and day-out to get by while they shoulder the burdens of complex, generational, collective, all-encompassing trauma. Stormont and Westminster alike have done little to meaningfully reconcile that legacy of conflict for several reasons: misunderstanding; indifference; a fear of stirring the pot; the electoral stability offered by polarized voting blocs; that urge to move forward that many of us feel, but for some is blinding. In much of Belfast, the truth remains “a circle from one side and a square from the other” (Jan Carson, The Fire Starters, p. 7), which concerns me.

If studying Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation taught me anything, it’s that the past (1) can’t be changed and (2) shouldn’t be ignored. After all, when one looks closely, it can reveal lessons about why conflicts begin, how they’re resolved, and the extent to which they transform the societies they affect. But the lessons don’t reveal themselves: we have complete agency to analyze the past, or to ignore it altogether. Sustainable futures are built on the foundation of a well-understood, respected, accepted past. That requires settling debts, rectifying power imbalances, acknowledging responsibility, searching for shared understanding, and creating opportunities for friendship. When we fail to build bridges and empower those most deeply affected by conflicts, “moving forward” actually means leaving scores of people in the dust. In the long run, that can perpetuate old inequities and create new ones, leaving a society in the same position as before, or worse.

Northern Ireland and its peace process no longer dominate media cycles like it did throughout the 20th century. International attention on the region climaxed with the ratification of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement (1998), which ended the Troubles and created the conditions for Mitchell Scholars, including me, to be sent to this wee island. Progress on the island, both positive and negative, has advanced in relative silence. Little attention is given to those who were adversely affected by the Troubles now that the armed campaigns have been suspended, even though their Troubles-related needs persist. Even less is given to the countless civil society organizations whose cross-community education programs, art initiatives, and history projects are on the cutting edge of bottom-up peacebuilding. Positive progress seldom makes headlines, while incidents of violence are quickly circulated around the world. Peace, like violence, is a verb. It does not suddenly arrive when a treaty is ratified. Peace is time-consuming, painful, introspective, and dynamic. But, over time, small gains accumulate to one day reveal a more peaceful and inclusive society. Like our individual lives, that society resembles a vibrant mosaic.

Despite the remaining obstacles to peace, Belfast has made tremendous progress since 1998. The fact that widespread violence is no longer a feature of daily life is a tremendous step in the right direction. Another positive development is that unionists and nationalists share power in an Assembly that, despite its repeated suspensions, is as productive as the other devolved United Kingdom legislatures (in terms of legislative output; see McEvoy & McCulloch, 2023, p. 25). The population of Northern Ireland has also been growing and changing since 1998. That change has primarily been driven by an influx of non-British Isles immigrants and the growing tendency, particularly among young people, to not identify as strictly unionist or nationalist. These indicate a society in which sectarianism is softening, if not eroding, to a certain extent, and one that can tackle bread and butter issues.

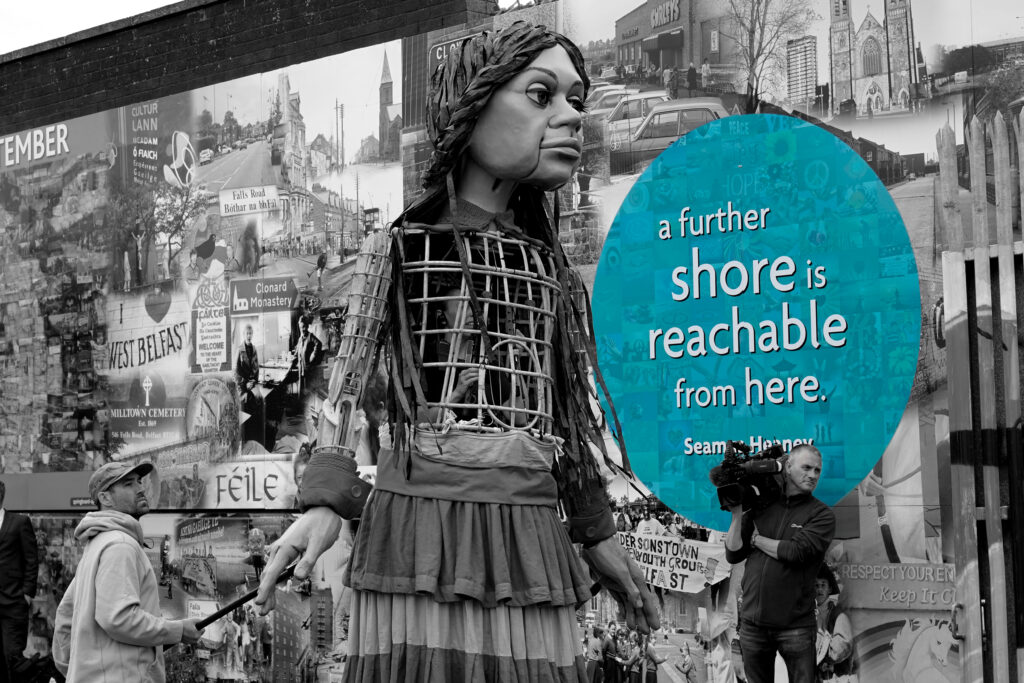

Evidence of positive change was most clearly illustrated to me when Little Amal visited Belfast earlier in May. This large puppet, depicting a Syrian girl in search of her mother, personifies human rights and the issues faced by displaced people worldwide. On behalf of Shared Future News, I provided coverage of Little Amal’s stops at Custom House Square, the Shankill/Falls peace line, and Colin Glen. The puppet expressed a surprising depth of emotion that was powerful in its own right, but was amplified by the people and places with which she interacted. In what I feel was the most memorable moment, Little Amal accompanied two groups of schoolchildren (one from the Shankill Road and one from the Falls Road) to the peace line interface, where they met, hugged, and chatted for a time, before returning to their respective sides. I discerned at least three levels of symbolism from this event: (1) the schoolchildren’s enthusiasm showed there is hope for sustainable cooperation and further change; (2) their return to their respective communities showed that segregation, and more general polarization patterns, still influence young minds, and; (3) collaborating on global, cross-community issues, like migration, to build bridges is an immense opportunity. Overall, watching the people of Belfast welcome Little Amal with open arms inspired hope and brought tears to my eyes. I consider it to be the most valuable out-of-classroom experience I had on the island, which I expect to linger in my memory long after I leave here.

I spent the last couple of months finishing up my courses. Now, I turn to my dissertation research, which will consume the rest of my summer. Thankfully, the last couple of weeks helped me settle into the right mindset for that work. I just spent the greatest moments of my Mitchell year with my family, the most important people in my life, in this home of mine. Today, I sent my grandma Marie, my cousin Joey, my brother Liam, and his girlfriend Hannah back to California following their seven-day stay on the island. We spent one day in Dublin and another on a bus tour of the northern coast, but we otherwise spent our time sightseeing in Belfast. I had seen most of our stops already, but touring them in the company of my family imparted a whole new meaning that I’ll cherish forever. This week, in the words of Sally Rooney, felt “like watching a perfect goal, like the rustling movement of light through leaves, a phrase of music from the window of a passing car. Life offers up these moments of joy despite everything” (Normal People, p. 228). I was also reminded of everything I felt on my own first visit to Belfast, which brought a goofy grin to my face all weekend.

It’s fitting that I wrote most of this blog post in the café of Belfast City Hall, the first building to catch my eye in 2019. I can’t remember any quotes from that first visit to the city, or anything else from that entire trip, to be frank. Neither can I pinpoint the exact moment my passions, tools, and questions converged on this spot of green. But in Cacophony of Bone, Kerri ní Dochartaigh offers a great suggestion to help me remember the experience: “REMEMBER THE LIGHT” (p. 27). I remember the way the light shimmered in the puddles of that rainy day during 2019. The glint of the graffitied peace walls. The bold colors of the flags, banners, murals, and memorials dotting the city’s segregated neighborhoods. The rays of sunshine trying, futilely, to break through the dreary overcast that so heavily coated the sky. I can’t articulate why, but those images stick with me today, dredging up every possible emotion one could experience. The urge to preserve those moments is a major reason why I followed in my dad’s footsteps and stepped up my photography game in Ireland.

Photography and peacebuilding have something in common, I’ve discovered: they both depend on light. A camera, technically, captures refracted light to digitally preserve as an image; that device also has to be operated by a photographer, who needs a combination of vision, timing, contextual understanding, and luck to capture a decent image. In much the same way, peacebuilding depends on light. The process is based on the assumption that a brighter future stretches ahead; one that former foes can share together; one that is inclusive, equitable, captivating, and peaceful. It also depends on allies of peace — us — to give what we can towards visualizing and producing that very future. Light is a tool that, when shed on the past, the present, and everything which is good, changes everything. And, to quote Victor Hugo, “even the darkest night will end and the sun will rise” (Les Misérables). Light conquers all.

Remember the light.