The role of a Director on a film set is more than just dictating the feel and look of the shots. It’s also about bringing the team together, making everyone believe in the common idea, connecting with the characters in your film and developing life long impacts on everyone involved.

With documentary filmmaking your story also follows a similar journey as in cinema – the heroes journey of triumph, defeat and overcoming obstacles, only in documentaries there is little you can predict in advance. Sure, you can create a script and force your narration in the direction you want, but for me, the beauty of documentaries is the unpredictability of the plot, of uncovering a puzzle piece to to an investigation, exposing the corrupt system with a smart question during an interview, and also giving a platform to speak for those who need it most.

Documentaries always leave you guessing where it will go next. That is why it is often hard for directors to determine the end point of the film – is there more to the story, is it a good enough ending, does it connect and intrigue the audience well enough?

My creative projects this year were filled with excitement and community around me. I got to be the director and cinematographer on all of my films and creative outings:

Inside Lisa’s projects

First ever project in Dublin – a profile story on my Master’s colleague from Nepal, Aashish. We were tasked to tell stories of each other – assigned randomly on the first week, we spend the whole semester understanding each other’s life stories and deciding how to portrait it in a film. I wanted to show Aashish as a musician, photographer and just a man in love, with his heart divided between two countries.

Through Nepalese Eyes

“Inside the Artist’s studios in Dublin,” a sneak peak into artists lives behind closed doors. I followed 15 artists from 10 different studios in Dublin to share their stories through film and video:

To watch the first short film:

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DKPq_xno8Ct/?igsh=Zjlrd3U1dXYxMDd1: Lights, Camera, Action!

Street photography inspired by Philip-Lorca diCorcia street photography. Capturing Dublin streets with a Speedflash 430ex 3-rt and CanonR6 Mark2:

Behind the scenes- my favorite spot right next to the camera!

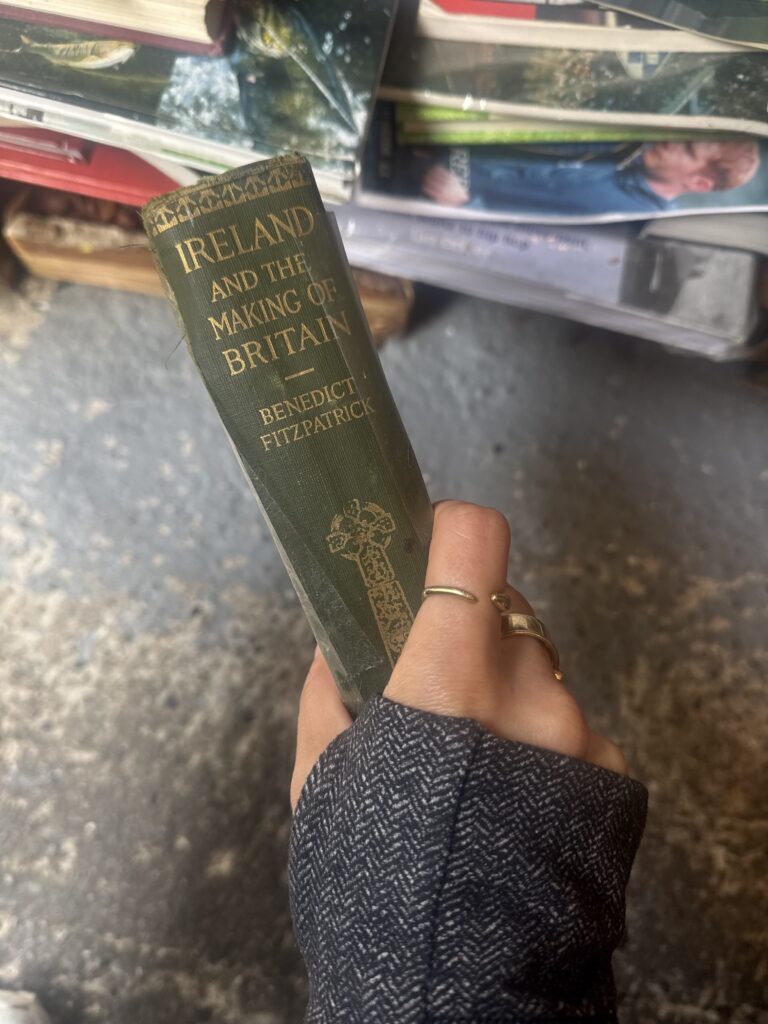

For my photography class I had to take photographs that represent main principles of photography (rule of thirds, lights and shadows etc) Mine turned out into postcards from Ireland series. My 10hour hike and a small Kodak camera with a theme for the day- imagine you only have 20 shots to take, what moment would you consider worth photographing?

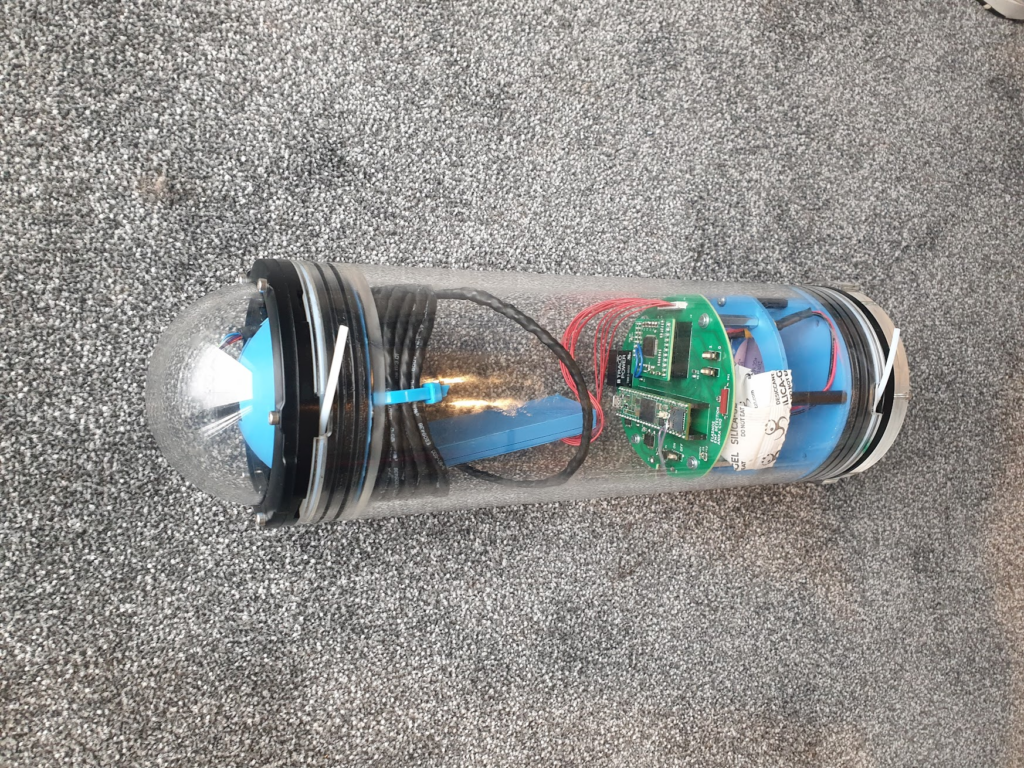

How our final Documentary projects are going for my Masters in Documentary Practice:

Behind the Scenes of our practice drone shots for our upcoming documentary “The Cost of Asylum”

To watch the BTS video and more, check out my instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DJ7Q8EnI6mt/?igsh=MXg3YmJlanZnZjRpaw==: Lights, Camera, Action!

I got to photograph and film a promo for a gallery opening in Dublin city center – Graphics Studio Gallery:

Check out how the video turned out:

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DJmEIbdOIwJ/?igsh=MWU3aHZsdnhtMmd5ZA==: Lights, Camera, Action!

A trip to Galway and stunning Ireland:

My love is food and film, I have been cooking so much recently and it brings me true joy when I get to host people for dinners:

What can I say? Ireland is my third home now, after Moscow, Russia and Norman, Oklahoma. I am forever grateful for Trina Vargo and the Mitchell Scholarship for giving me the opportunity to live in this gorgeous country and become the filmmaker that I am today.

Please come to our Documentary Screening in Dublin in July and watch out for our films at IFI!

And finally, I want to share a documentary that was made about me by my course’s colleague, Claudia that did a profile piece on me: