Some years ago, I saw and heard the Irish music group “Ghost Trio” perform the song “Cucanandy.” This was in the era of live music. The song chilled me to the bones. (This was before chills were symptomatic.) It has haunted me ever since. And now, in these dark days, it reemerges for me again, eerily apropos, playing silently in my head while (I imagine) roaming the (locked-down) landscapes where it was born some unknown time ago.

As a traditional song, the origins of “Cucanandy” are wonderfully unclear, as if it emerged from the salt of the earth itself. Many notable Irish folk singers claimed to have had it sung to them by various female members of their families as they were growing up. Indeed, the song is recognized as a “dandling song”—a song to accompany the moving of a baby up and down on one’s knee, an affectionate vertical rocking. Perhaps this is why it’s so haunting: the song emerges from the grooved recesses of infancy, that alien being we all once were and never can remember or return to.

Although I doubt my American parents sang this particular song to me as an infant, I can’t be sure, and in any case the song has the crystalline melancholic lilt of any good lullaby. This may explain why many Irish singers, even in vastly different regions (before information was instantaneous and sharing virtual), improbably claim to remember the same song from their childhoods: it is made of the stuff—the overwhelming love, the promise of comfort, the yearning, the loss already emergent if not yet arrived—of lullaby.

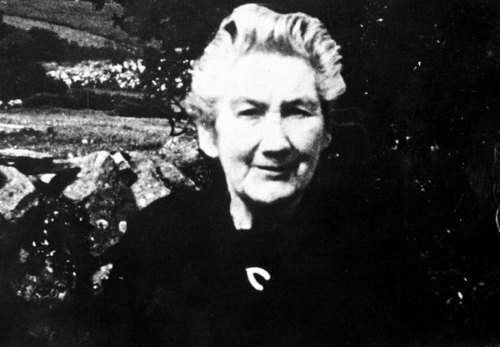

We can hear versions of the song today thanks largely to Elizabeth Cronin, an influential traditional Irish singer born in 1879 in West Cork. In late January of 1951, almost exactly 70 years ago, when Cronin herself was in her 70s, ill and ailing, the American ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax brought a microphone to her bedside and she intoned a version of “Cucanandy” that exists to this day. It is marvelous to hear it: a voice from the 1800s, recorded in the middle of the last century, singing just before the shadow of death a song for the liminal time just after birth. Because, as the contemporary Irish writer Niall Williams observed in his excellent novel This Is Happiness, “as you get toward the end, you revisit the beginning.”

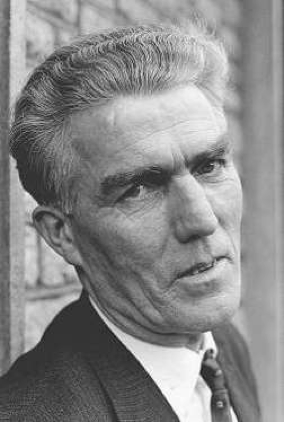

Later, the singer Joe Heaney (in Irish, Seosamh Ó hÉanaí), born 1919 in my own County Galway, and died 1984 on my own United States west coast, recorded another version of the song for another folk music archive. Heaney moved to the US in part because he thought his sean-nós singing (Irish for “old style”) was better appreciated there than it was in Ireland. The oral, a cappella tradition of sean-nós emerged largely in response to various historical British efforts to crush Irish culture by confiscating traditional instruments. The voice, after all, cannot be stolen.

The song title “Cucanandy” is nonsense as far as Cronin and Heaney knew. Often the song is sung in a medley with other tunes, as in Heaney’s recorded version. The lyrics vary with each iteration. They meld Irish and English language. And, as we’ve seen, in a series of ghostly reverberations, they meld together a larger story about Ireland, the United States, even the history of British imperialism (my course of study here).

The version of the song that hooked me, by the Ghost Trio (itself named after a Beckett play) and later The Gloaming, is not apart from those interlinkings. (None of us are.) The lead singer Iarla Ó Lionáird had Elizabeth Cronin as his great aunt. Her voice is, almost literally, within him.

I’ll close with the verse that seems always to appear, and haunts me so, simple and profound:

Throw him up, up

Throw him up high

Throw him up, up

He’ll come down by and by