“Memory is random and irresponsible in every heart” (Kate O’Brien, 1938).

Last month, I FaceTimed my girlfriend for a virtual date night. We chatted about her upcoming college graduation, and she described excitedly how frenetic and chaotic the home stretch would be. She was looking forward to all the “senior week” events, eager and optimistic to make some core memories before leaving Boston. I reflected on my own pre-graduation senior week from a year ago and thought about the core memories I have—picking up my cap and gown from the gym, views of the skyline from a parking deck during a photoshoot with my friends, the cookies served on the party boat in Boston harbor, the sun’s heat I felt waking up from a nap instead of attending commencement.

What makes a moment become a core memory—the kind of memory that pulls you into the past, that you can describe in excruciating detail? Some core memories capture life-changing moments, yet others are rather innocuous. Maybe you remember vividly the scent of a bagel shop that you grew up near, or maybe the booming voice of Boston’s MBTA system warning you to “stand clear of the closing doors” takes you back to rush hour commutes for your first job. Some core memories are moments we cherish and return to—a first date, a college graduation—and other core memories we bury and try to forget. But if the moments we remember aren’t dictated by the moment’s significance, or a person’s affect toward it, or even its recency, then what does determine how we form core memories?

Earlier this semester, I had the privilege to hear Geoffrey Hinton—winner of the 2018 Turing Award and creator of backpropagation—deliver a seminar on artificial intelligence at UCD. Hinton is a cognitive neuroscientist who fell into AI curious about its human mind-inspired design. When asked about whether he believed large language models could be as creative and inventive as human research scientists, he answered:

“A lot of creativity comes from seeing remote analogies.” Neural networks, like humans, find analogies and patterns between distant ideas that allow concepts and language to be compressed in a finite number of neurons. This is how GPT can, for instance, creatively answer how a trash compactor is similar to a backpack.

To learn with a finite number of neurons all that it encounters from billions of training examples, a deep learning model identifies common, generalizable ideas. Does human memory work analogously, recognizing similarities between disparate experiences to capture them within a finite number of neurons?

Dr. Tomás Ryan is a neuroscientist at Trinity College Dublin who studies this mechanism of human memory in engrams—neuronal ensembles that tune what they’ve learned through persistent physicochemical changes. His research suggests that new experiences aren’t learned from scratch, but broken down into ideas which have already been learned, and those corresponding engrams are tuned via long-term potentiation or depression, which is analogous to how Hinton’s backpropagation algorithm enables adaptive changes to neural ensembles.

So given what we know about how memories are effectively stored in humans and machines, maybe core memories possess some “dis-analogies” where something unexpected occurred or something new was discovered. Maybe the strongest core memories cannot be effectively stored, requiring more neuronal ensembles to capture and recall the moment.

I contemplated this in the context of my Mitchell year, and realized it held true for many of my clearest memories. In a year dotted with rare experiences and unbelievable beauty and unanticipated growth, the moments that I remember clearest include some element of relative normalcy—eating PB&J’s with Zach, Rabhya, and Teresa atop magnificent Glendalough; the cold, dewey grass we sat on at St. Stephen’s Green after meeting Senator Mitchell; the soreness in my legs running 12% elevation to Conor’s Pass by Dingle.

In a moment of clarity, I realized it’s the juxtaposition of simple experiences with rare ones, slow experiences in chaotic times, and moments of connection amidst isolation that formed my core memories as a Mitchell.

I think a false belief I held coming into Dublin was that living the most colorful and memorable life meant aspiring for summits or picturesque cities or accolades or something grandiose. And while pursuit of that thing can be worthwhile, constantly living within it may not be what you remember or appreciate best when you leave.

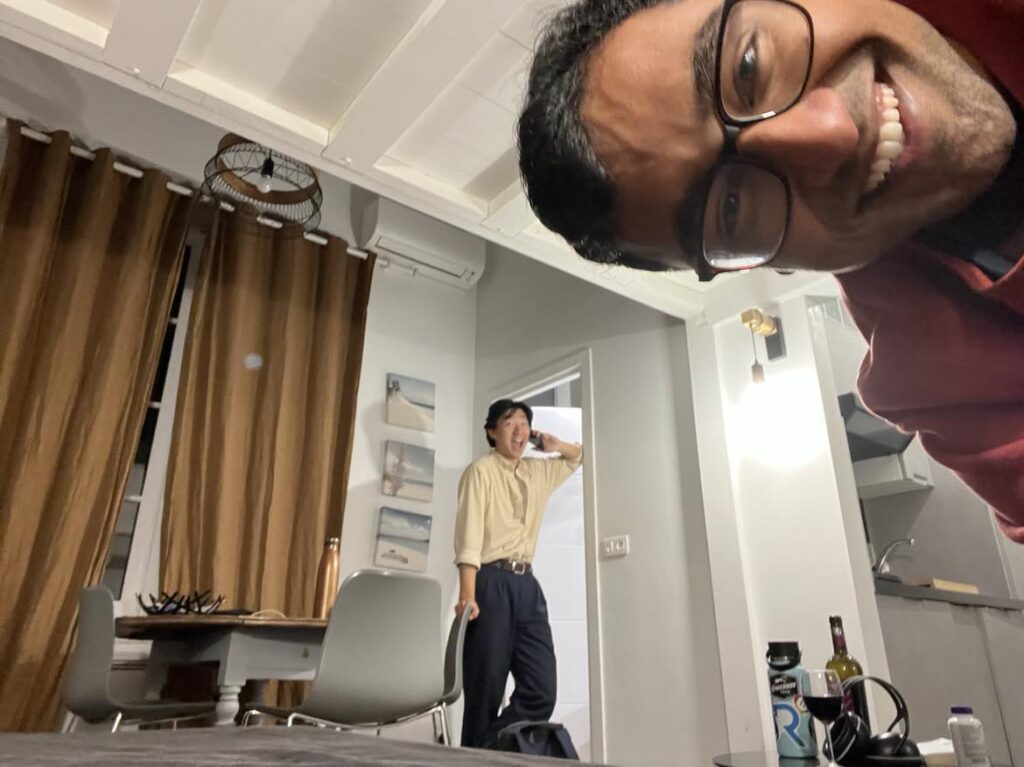

My roommate and closest friend in Dublin is Anthony (Yan), an Information Systems student from Northern China. Anthony returns to China next month, and while getting dinner at a noodle shop, I asked Anthony: “When we first met this year you said you really liked the expression ‘no risk, no story.’ Do you think you have a story now?”

“Mmmm, I think so. Before coming here, I never left my hometown. Now I am in a new country, speaking a new language, and I meet new people, and I see new things. So I think yes, I have such a good story to tell. I think with no risk, there is no story. But also, the risk is the story. I think when I’m older and maybe I’m stressed about work, I will remember about this time we spent together in Ireland, and I will remember when we went to the City Centre to eat noodles, even though it is very simple. But this is where my life happens, and this is a beautiful moment.”

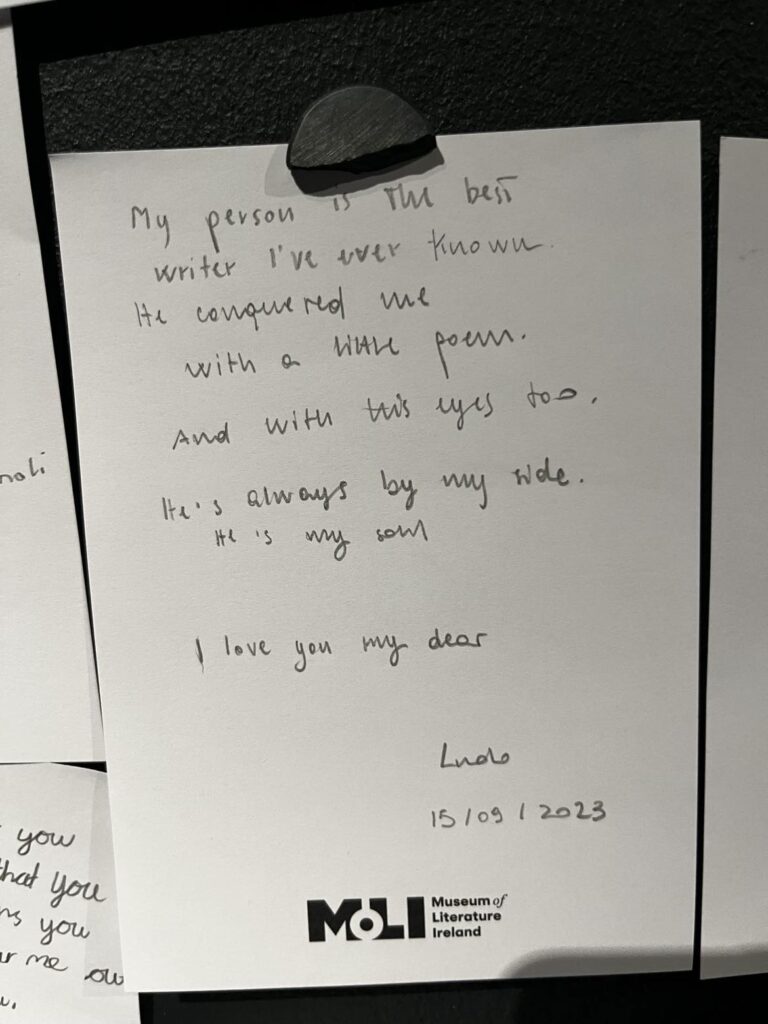

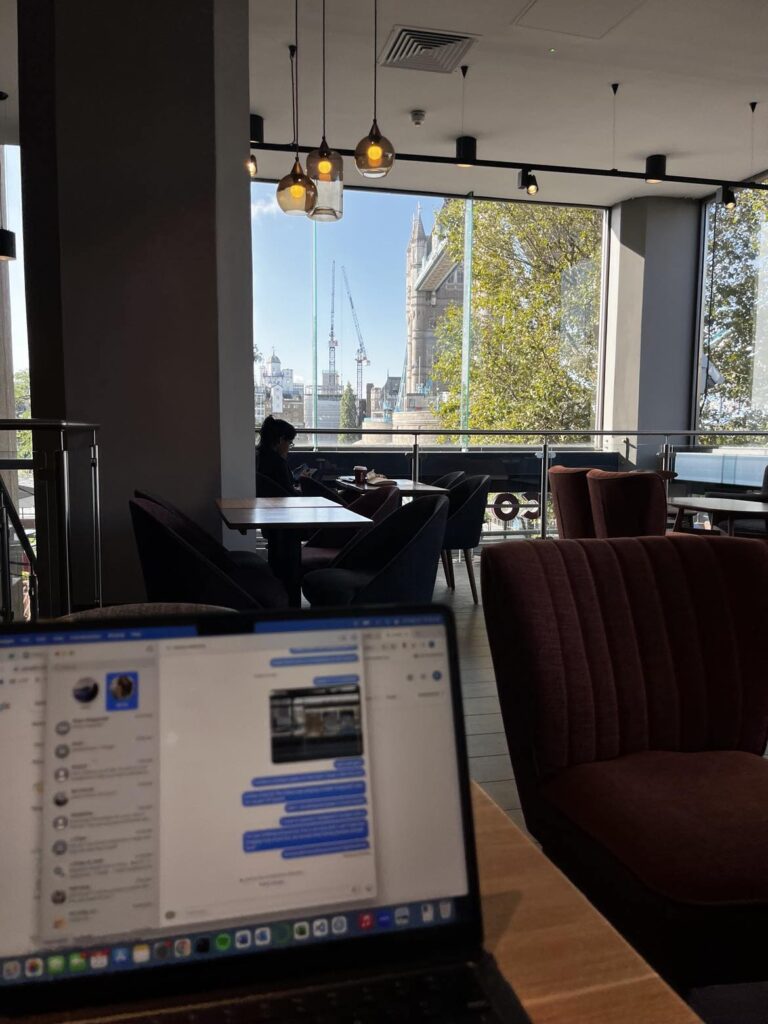

One of my closest childhood friends once innocently captioned an Instagram post, “the moments between the moments.” Ripping a page from his book, here are some images that capture the moments between the moments from my year in Dublin: some of my fondest, most cherished core memories.

“I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Maya Angelou