An odyssey across my many encounters with an iconic Derry building

I first met the Guildhall of Londonderry on the night of Halloween. An early evening of torrential downpour made way for clear midnight skies, and between the parting clouds, I saw the hall’s clock tower.

Tall and orange.

(But mostly orange.)

That orange clock face watched quietly over the festivities that evening, its neo-gothic façade blending into the rest of the town’s elaborate Halloween decorations. But despite its foreboding exterior, the Guildhall seemed to invite me back.

I returned to the Guildhall of Londonderry less than two weeks later, on the second Friday of November. That night, Derry was the second stop on a winding expedition from Dublin to the village of Burnfoot in County Donegal. But at nearly an hour past midnight, we were fatigued and famished. Our attempts to flag down a train station taxi willing to drive us to the village proved futile, but across the River Foyle, I spotted the tower of the Guildhall beaming back at me.

We made our way across the Peace Bridge to the Guildhall and to our delight found a 24-hour Kebab House just across the square. Sat on the freezing stone blocks outside the hall and scarfing down chips before the seagulls could snatch them, we called a cab from one of the two taxi company phone numbers the Kebab House employee had recited for us from memory.

The next morning, we returned to the Guildhall with the intention of stepping inside. Before we made it through the entryway, however, we were stopped in our tracks by the Queen of Hearts. Or rather, we were blocked by a woman in a stunningly elaborate costume of the Queen of Hearts. As we looked out onto the square, it occurred to us that nearly everyone in the square was dressed in high-quality Alice and Wonderland costumes. After mustering up the courage to ask the Queen of Hearts why everyone in Derry had seemingly stepped out of the storybook, she clued us into the city-wide outdoor puzzle game running that day hosted by a puzzle app. How nearly the entire city—from the infants in Cheshire Cat onesies to the Queen of Hearts herself—managed to pull costume-quality outfits for the sake of an app’s puzzle game remains a mystery.

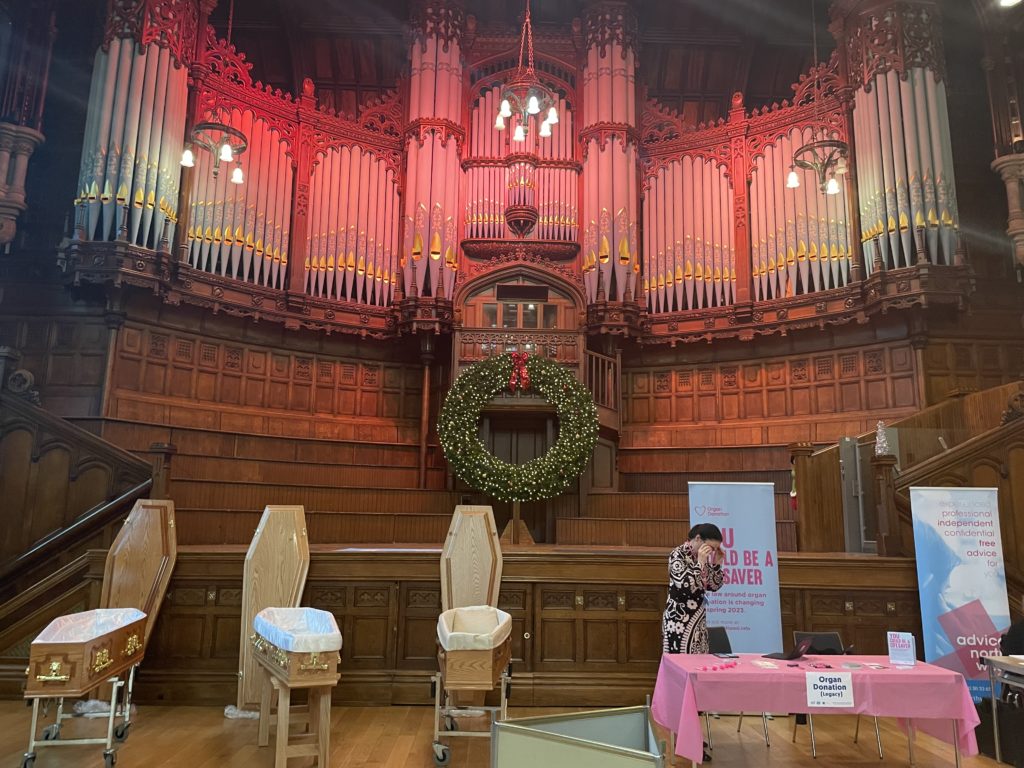

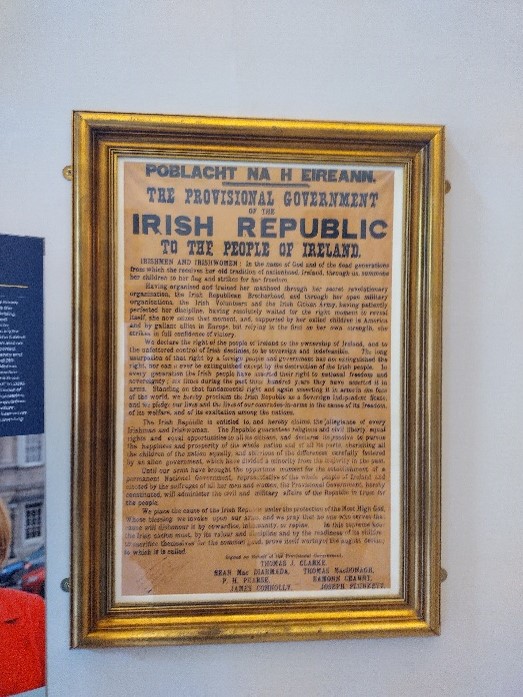

We eventually entered the Guildhall where we were directed to some stained-glass artwork and an exhibit on the building’s history. It detailed the building’s completion in 1890, its clock tower modeled after London’s Elizabeth tower, the terror attacks during The Troubles that destroyed most of the original building, and the city council business occurring inside through the present. Upstairs we stumbled upon the main hall with its historic pipe organ where a funeral fair was just wrapping up. Empty caskets for sale lined the room along with booths on various end-of-life topics. And the organ was already decorated for Christmas.